The View from Here

Stieglitz at the National Gallery of Art

Margaret Regan

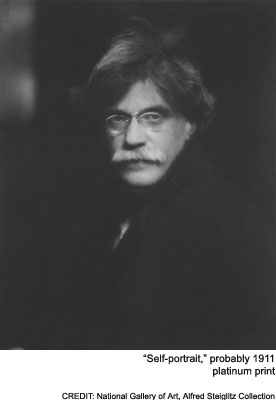

Margaret Regan When pioneering photographer Alfred Stieglitz died in 1946, painter Georgia O’Keeffe spent three years putting her late husband’s mountains of pictures in order.

When pioneering photographer Alfred Stieglitz died in 1946, painter Georgia O’Keeffe spent three years putting her late husband’s mountains of pictures in order.She didn’t have to edit as much as might be supposed. The photographer himself routinely destroyed prints he considered failures, so much so that on numerous occasions O’Keeffe had felt obliged to save work from the dustbin. And as Stieglitz grew older he deliberately culled his pictures with an eye toward shaping his modernist legacy. Still, after his death, there was a lot to do. Casting about for a museum to house his mounted prints, O’Keeffe quite naturally approached the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the city Stieglitz had so often celebrated in his pictures. But O’Keeffe was horrified to learn that the Met’s curator, in order to fit the new acquisitions into the museum’s standard storage boxes, intended to trim Stieglitz’s carefully cut mount boards.

The painter knew that the photographer didn’t consider the print a suitable art object until it had been mounted, and she had no intention of allowing the desecration. The story goes that Met officials explained to O’Keeffe that even Rembrandt’s prints were subject to the slice-and-dice treatment. As O’Keeffe later told the Stieglitz scholar Sarah Greenough, she drew up her formidable self and replied, “Well, Mrs. Rembrandt wasn’t around to complain.”

The National Gallery of Art apparently promising not to maul Stieglitz’s handiwork, O’Keeffe gave the entire collection to the then fledgling Washington museum. The pieces “formed what she called the key set&Mac226; of his work, including at least one print of every mounted photograph in his possession at the time of his death,” according to an essay by Greenough. This treasure amounted to some 1,300 photographs that O’Keeffe donated in 1949, and another 325 or so—all portraits of her—that she gave in 1980, not too long before her death in 1986. The Met’s proclivity to wield knives worked to the National Gallery’s advantage: the key set in Washington is the only one known.

Last summer, Greenough and the National Gallery drew on the key set for a handsome show called Alfred Stieglitz: Known and Unknown; some works on exhibit got a public airing for the first time in 50 years. The show also marked the publication of a massive volume called Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set, a two-volume work that for the first time reproduces every single image in the key set. Obviously, any exhibition would be able to draw on only a small portion of the 1,642 photos in the key set, but the 102 works shown traced Stieglitz’s long career from late Victorian Europe to America at mid-century.

Last summer, Greenough and the National Gallery drew on the key set for a handsome show called Alfred Stieglitz: Known and Unknown; some works on exhibit got a public airing for the first time in 50 years. The show also marked the publication of a massive volume called Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set, a two-volume work that for the first time reproduces every single image in the key set. Obviously, any exhibition would be able to draw on only a small portion of the 1,642 photos in the key set, but the 102 works shown traced Stieglitz’s long career from late Victorian Europe to America at mid-century.If O’Keeffe’s hand in bringing about the show was invisible, her starring role as subject was not. Any Stieglitz retrospective would be incomplete without the photographer’s adoring portraits of the painter. He made more than 300 pictures of O’Keeffe between 1917 and 1937, when ill health forced him to end his long photographic career. Alfred Stieglitz: Known and Unknown duly offered up some 25 images of her. Astonishingly, they amounted to almost a quarter of the works on exhibit.

The early erotic nudes are ablaze with sexual fervor—the naked subject gazes at her photographer with frank longing, and the favor evidently was returned. In a frenzy that O’Keeffe later described as “a kind of heat and excitement,” Stieglitz made 140 studies of her in the first three years they were together. With his camera he lionized her long, lean body, and lovingly scrutinized her separate body parts, making arresting images of her hands, her breasts, her feet. Sometimes, as in the 1921 Georgia O’Keeffe—Hands and Grapes, he borrowed pieces of her anatomy for elegant still lifes. He considered these startling images elements of a single work, and exhibited them as a composite portrait called Woman (One Portrait) in 1921. The sadder, more sober portraits didn’t come until the 1930s, when the two were leading essentially separate lives, he in New York, she in New Mexico. In these later pictures, the bones and blankets of O’Keeffe’s Southwest life are positioned like barriers between photographer and sitter.

A groundbreaking modernist with an enormous influence on American photography, Steiglitz once declared, “I was born in Hoboken. I am an American. Photography is my passion.” Yet this show demonstrated conclusively just how much Europe influenced the American photographer. Born in 1864, Stieglitz moved with his family to Germany at the age of 17. Studying with photographers as well as painters, he early on made gorgeous photographic renditions of the genre scenes favored by conservative European painters. His workers laboring among wheat sheaves recall Millet, and his fisherman’s wives waiting on the shore summon up Boudin’s bourgeois bathers. The Last Joke—Bellagio, is a classic genre study—a carefully assembled group of peasants, rendered noble by art.

A groundbreaking modernist with an enormous influence on American photography, Steiglitz once declared, “I was born in Hoboken. I am an American. Photography is my passion.” Yet this show demonstrated conclusively just how much Europe influenced the American photographer. Born in 1864, Stieglitz moved with his family to Germany at the age of 17. Studying with photographers as well as painters, he early on made gorgeous photographic renditions of the genre scenes favored by conservative European painters. His workers laboring among wheat sheaves recall Millet, and his fisherman’s wives waiting on the shore summon up Boudin’s bourgeois bathers. The Last Joke—Bellagio, is a classic genre study—a carefully assembled group of peasants, rendered noble by art.These lovely 1880s pieces are painterly tonal platinum prints. Like the other Pictorialists, Stieglitz worked against the perception that photography was merely a technical medium, a humdrum copier of reality divorced from art. The Pictorialists sought to inject their photographs with arty high-mindedness—strong feelings, lovely compositions—and they crafted them with care, making them unique art objects. Nowadays these photographers come in for criticism for their sappy subjects, from sylvan frolics to sentimental madonnas, but they played a respectable part in pushing the idea that photography can be art. And truth to tell, while critics conventionally think of these early Stieglitz pieces as prologues to the work that was to come, their painterliness is fresh, and welcome. Not so coincidentally contemporary photographers have been experimenting with such cumbersome old technologies as palladium printing to achieve similar laudable effects.

America, naturally, was bound to change the young artist. In 1890, he returned to New York, a Gilded Age hotbed of capitalism, a bustling city growing architecturally toward the sky. The Flatiron building, he later recalled, struck him as “moving toward me like the bow of a monster ocean-steamer—a picture of the new America that was still in the making.” He photographed the bold new piece of architecture—his father called it “hideous”—again and again. The city was teaching him he could make art photography outside the straight-jacket of old-world subjects.

Even his pictures of working people changed. No longer did he photograph romanticized Old World peasants, the picturesque gleaners and fisher wives of his European genre works. Now he took on laborers in the new industrial city, low-status people considered eminently unsuitable as subjects for photography. Not long after his return, Stieglitz made The Terminal, one of his most famous pictures. It’s a wintry, thoroughly unromantic New York street scene—a carter watering his horses on a cold, gloomy day. Its darkness is pierced by the white of the snow sprinkled on the cart and street, and by the ghostly light of steam rising up from the horses. It details the labors of a grim life, but it is beautiful nonetheless.

Even his pictures of working people changed. No longer did he photograph romanticized Old World peasants, the picturesque gleaners and fisher wives of his European genre works. Now he took on laborers in the new industrial city, low-status people considered eminently unsuitable as subjects for photography. Not long after his return, Stieglitz made The Terminal, one of his most famous pictures. It’s a wintry, thoroughly unromantic New York street scene—a carter watering his horses on a cold, gloomy day. Its darkness is pierced by the white of the snow sprinkled on the cart and street, and by the ghostly light of steam rising up from the horses. It details the labors of a grim life, but it is beautiful nonetheless.Increasingly evangelical, Stieglitz embarked on a shadow career as a photography magazine editor, working successively on The American Amateur Photographer, Camera Notes and Camera Work. If he indulged himself by featuring his own work more than any other photographer’s, he believed he was rectifying a pitiful situation in his native land.

“When I returned to America I found that photography as I understood it hardly existed,” he once told Dorothy Norman. He fumed that Kodak was promoting a camera to amateurs with the slogan, “You press the button and we do the rest.” This was hardly the kind of art Stieglitz had in mind. His early magazines praised the delights of Pictorialism, and exhorted serious shutterbugs to inject art into their endeavors by studying the principles of painting.

Eventually he went right to the source. In 1905, he opened 291, a gallery named for its address on Fifth Avenue, with plans to instruct his fellow Americans in the avant-garde art of Europe. (291 was just the first of three influential Stieglitz galleries, which also included The Intimate Gallery and An American Place). He succeeded in stunning New Yorkers with pioneering painting shows of Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and Brancusi. These European artists returned the favor to their gallerist, pushing his work in ever more modernist directions.

Abandoning Pictorialism’s soft focus, Stieglitz began experimenting with shape and form, much as his cubist friends were doing. All-American New York was the perfect laboratory for his European-inspired endeavors, and its hard-edged geometries made their way into his pictures. He obsessively photographed from the back of 291, making cubist constructions of the city’s architectural volumes, and he abstracted its harbor and riverways. The well-known picture The Steerage, from 1907, aptly records the torrent of Europeans washing up on American shores, but it’s also an abstract composition of shapes—from the white straw boater hat to the diagonal pipe—that lend their geometries to a syncopated pattern of lights and darks.

Abandoning Pictorialism’s soft focus, Stieglitz began experimenting with shape and form, much as his cubist friends were doing. All-American New York was the perfect laboratory for his European-inspired endeavors, and its hard-edged geometries made their way into his pictures. He obsessively photographed from the back of 291, making cubist constructions of the city’s architectural volumes, and he abstracted its harbor and riverways. The well-known picture The Steerage, from 1907, aptly records the torrent of Europeans washing up on American shores, but it’s also an abstract composition of shapes—from the white straw boater hat to the diagonal pipe—that lend their geometries to a syncopated pattern of lights and darks.Stieglitz was clearly drinking up the lessons of modernism—simplicity, form, volume, light and shadow are paramount in these works—but their ships and buildings are still recognizeable. In his 1920s cloud pictures, he dipped much deeper into abstraction. One story goes that a critic had remarked that anyone could make a picture beautiful when the model was as striking as O’Keeffe; in response, Stieglitz decided to make photos equally lovely out of the ephemera of clouds. More seriously, he was trying to use his new subject to express internal feelings. First he called the series “Songs of the Sky” but eventually he settled on “Equivalents,” noting “I have a vision of life and I try to find equivalents for it sometimes in the form of photographs.” A hand-held camera, at 4 by 5 inches substantially smaller than his 8 by 10 view camera, allowed him the freedom to aim easily at the sky. Unanchored by a horizon line, the shapes drift across the photographic plane in these pictures.

He also occupied himself with the landscape below the clouds, particularly at his beloved summer home in Lake George, New York. Moving toward what Greenough calls more “intuitive” work, he approached the lovely countryside in ways that O’Keeffe and the painters Arthur Dove and John Marin had already tried. Rural upstate New York also provided a setting for snapshots of family and friends that are probably the most informal work this deliberate photographer ever made. These pictures are loose and cheerful: among them can be found a laughing Rebecca Salisbury Strand, wife of the photographer Paul Strand.

Stieglitz’s influence on American photography is immeasurable. Acting as both evangelizer and artist, he almost single-handedly persuaded the public that the new medium was an art form. He labored tirelessly in his journals and galleries to press the point, and his own works served as an irrefutable example of the principle. They’re one-of-a-kind art objects, gorgeously composed, exquisitely printed —and beautifully mounted!

But photography eventually evolved without him. By the 1930s, the disorders of the Depression were inspiring photographers to right social ills through social-realist documentary. Steiglitz’s high-falutin experiments had begun to seem elitist and out of step, the curator tells us. His health was declining, his relationship with O’Keeffe eroding. Nevertheless, he spent his seventies making important urban pictures of the quintessential American city and elegiac pictures of the American countryside.

“Literally and metaphorically more focused,” Greenough declares, “these (late) photographs reverberate with a sense of time and change, and with memories of the past.”

For information on the publication Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set, call the National Gallery of Art at 1-800-697-9350 or visit the website at www.nga.gov/shop/shop.htm. The book is in two volumes, and reproduces all 1,642 pictures in the National Gallery’s key set. It includes an introductory essay by Sarah Greenough and appendices on Stieglitz’s techniques and processes.

Margaret Regan gratefully acknow-ledges consulting Greenough’s essay and the museum’s wall text for some of the information in this article.

- Margaret Regan is a freelance arts writer specializing in photography; she lives in Tucson, Arizona. She is the co-author of Steven Meckler Photographs Tucson Artists, published in 1995 by Black Spring Books, Tucson. Her work has appeared in Make A Journal of Women's Art (London), Newsday (New York), New Village Journal (Berkeley, California), Hurricane Alice (Ann Arbor, Michigan), Black & White (Birmingham, Alabama), and in the Tucson Weekly, Arizona Daily Star, Tucson Citizen, Tucson Guide Quarterly and Phoenix Home and Garden. She has won 23 journalism awards for her work, the most recent for a two-part look at Arizona’s pioneering women architects.